post 3 in the Navigating Academic Publishing series

For the third post of the series Navigating Academic Publishing, I offer an in-depth overview on journal articles. In our last post, we distinguished a journal article from a seminar paper and talked about how academic writing is more than just course assignments. Now, let’s turn to the most common mode of scholarship: the journal article.

What is a journal article?

Journal articles are the “bread and butter” of scholarship and what most of us engage most frequently. Articles tend to be one-offs or standalone essays that seek to intervene in extant scholarship to make a valuable, novel contribution. But “contribution” isn’t a one-size-fits-all term: the hidden norms of your discipline shape how interventions are made. In Communication and Rhetoric, a contribution might look like (1) a new theoretical lens or critique, (2) a historiographic intervention or recovery, (3) methodological innovation or refinement, (4) launching a new archive or area of inquiry, or (5) applied recommendations for communication/rhetoric professionals. A way to ensure your submission reaches review and press is to always ask yourself, “How can another scholar take this up? How could they cite it? Where would it fit on a syllabus? Why would it be taught/assigned?” This approach will keep the contribution facet of scholarship front and center for you as you craft the essay.

For an essay to see press, it must go through the submission process of the journal. Articles are most commonly “cold submissions.” These submissions are essays that have not been invited by the editor, nor does the editor have much/any context on the submission prior to reading the cover letter. Other articles can come by invitation or other means, but most of the time articles are submitted cold. Even as a genre, journal articles come in a variety of iterations. Here are the most common five in my areas of research.

- Original Research Article

- Research articles are the most common within the academy, and include offering an original intervention into the discipline. Most often includes either original data and/or original interpretations of data. When you think of a <journal article> it is usually a research article.

- Original Research Articles are only constrained by a journal’s aims and scopes, word counts, and style guidelines. It is incredibly important to check all of these before submitting to the journal. It will be under their “information for authors” or “submissions” tab on the website or database page.

- Subject to anonymous review, always. Most journals tend to begin with two reviewers per submission; however, if those two reviewers offer two opposing reviews, a third may be asked to review the article to “break the tie,” so to speak.

- Special Issue Article/Contribution

- While similar to an original research article, these articles are slightly different as the topics will be constrained to a particular area or method. Special Issues tend to be interdisciplinary by design—e.g., a gender studies journal will seek scholars from across humanities, arts, social sciences, and hard sciences, etc. However, they can be siloed to a specific discipline with a unifying keyword or theme—e.g., a comm journal doing an issue on “liberation” or a “keywords” special issue.

- The focus and parameters for the issue will be announced in a Call for Papers. Timelines will usually also be given in the call. Not all special issues will operate on a call for papers, but rather on an invitation. Some special issues are also proposed to the journal with authors already attached. It can vary.

- The submissions to the issue will have guest editors who guide the essay through the review process. These editors will be the arbiters of decision more directly than the “editor in chief” of the journal. But the review process is the same as that of an original research article.

- Forum/Discussion Contribution

- These are akin to a mini special issue within a “regular” issue of a journal. Fora articles tend to be shorter than the “usual” article from the journal.

- The forum or discussion will often focus on a specific by topic, respond to a specific event within or important to the field, and/or operate as a roundtable of sorts.

- Fora can either be invitation-only (where the coordinator of the forum contacts individuals to contribute) or an open call—or a blend.

- Peer review for these can either remain the same (two anonymous reviewers), or they may only go through the forum/discussion editors, or another form of review.

- Calls and/or invitations will outline the review process.

- Journal-Specific Options

- Some journals will offer other kinds of articles. For example, pedagogy journals will often have a “share a lesson plan” style contribution that may also be a less daunting entry point than a full independent study/article.

- These will undergo the same peer review process, but will likely have an amended set of parameters the reviewers consider.

- Book Review or Review Essay

- These are an excellent place for new scholars to get experience with a streamlined version of the editorial process.

- The submission of a review essay can either happen in a portal, like an original research article, or an editor might prefer doing initial feedback via email.

- Often, only the reviews editor will offer feedback and suggestions on the review essay as the means of “peer review.” The essay will then go to copyeditors and see page proofs like any other article submission would.

- Book reviews are the most common, but some venues do offer film, performance, art, and/or other review essays. Some reviews can also tackle more than one work at a time.

- All reviews will include a summary of the arguments/contents, how the discipline benefits from the work, and a gentle critique of the work. Most are under 2,000 words, but check journal guidelines.

- These are an excellent place for new scholars to get experience with a streamlined version of the editorial process.

What is journal “prestige”?

You may hear a handful of terms categorizing journals based on their “status” or “prestige” in the field. There are multiple ranking systems for journals (e.g., impact factor, h-counts, etc.), but there are other common markers that are more qualitative in nature.

The most important thing when considering a journal is the fit for the article. Once a fit is determined, then you can parse out “prestige,” if you so desire. A strong article is a strong article no matter the venue, and a venue with a better fit will likely emphasize the strength of the article.

The table offers some of the more common designations for journals. These terms are very slippery and, with the distinction of association or non-association journals, can overlap in different ways. The table is roughly arranged in order of preference for tenure review and job search committees. But this is not hard and fast.

| Categorization | Import | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Association Journal | Tied to specific disciplinary associations, e.g. National Communication Association or Rhetoric Society of America. Typically a higher commitment to fostering emerging scholars. These journals are also typically preferred by tenure review. | See: NCA Journals, RSQ: Rhetoric Society Quarterly |

| Non-Association or independent journal | Not tied to any specific association in the field. They are housed by university presses, often, and will be headed by scholars in the field. Some hold commitments to fostering new scholars but it is not as expected as association journals. | See: Rhetoric and Public Affairs, QED: A Journal of GLBTQ Worldmaking |

| “Flagship” | Often the longest standing publications in each field. Will hold submissions to the highest level of critique. (Have likely had name changes in it’s history.) | See: Quarterly Journal of Speech, Language & Society |

| Topic/Subfield Specific | Specific to a discipline (e.g. communication) but constrained the focus of all submissions to a specific sub-area or topic within the field. | See: Women’s Studies in Communication, Communication & Race |

| Interdisciplinary | Cross disciplines and focus on a range of topics, theories, and methods. Peer review here will often feature incorporating new-to-you literature. | See: WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, Cultural Studies |

| Regional/Local | Often siloed to a specific discipline but open methodologically. These venues tend to prefer localized content to the readership. Some of these are tied to regional associations. | See: SCJ: Southern Communication Journal, PA Communication Annual |

| Early Career Focused | Specifically target early-career faculty and/or graduate students. Go through the same peer review process and aimed at professionalization. | See: Kaleidoscope, Deliberately Queer Journal |

Why journal articles?

Articles, in the overall schema of academic publishing, tend to be the most accessible form of publishing to both author and reader. For readers, they often will have access as part of their library’s databases and/or it’s easier to share an article peer-to-peer than other forms of publishing. There is less likelihood of a reader having a direct cost associated with accessing an article, versus a book. For authors, it is the most accessible for a handful of reasons:

- The submission is a standalone essay rather than a multi-chapter book project that requires multiple levels of coherence and intervention. (Articles are also an excellent way to seed part of a book-length argument in more digestible segments.)

- Most journals are long-standing and/or tied to long-standing institutions, which means there’s a higher likelihood of an accepted work seeing print sooner than books. Particularly in edited collections, there are many different variables that can end up thwarting or delaying publication.

- Most journals are implicitly expected to foster professionalization of emerging scholars, so you’re most likely to get feedback from a journal—especially one tied to a disciplinary association, e.g., NCA journals—than other kinds of submissions.

- Journal articles are staples of most upper- and grad-level syllabi, meaning you have a broader audience for your potential work. Books require a greater reader investment (monetarily, temporally, mentally) than a journal article, lending to a greater chance of being read. Presence on syllabi is also helpful to prove/have in tenure review.

This ease of access does not mean publishing journal articles is quick, painless, etc. Any and every kind of research takes time, drafting, revising, and workshopping. Articles are no different.

The generalities of an article

The ultimate format/structure of your article will vary slightly based on the topic and the journal it’s being submitted to, but most full-length articles will have:

- Title page with identifying information (name, affiliation, bio, contact), and the word count.

- A second page with your article title, the abstract, and keywords. The essay text begins on that same page.

- The essay will more or less follow the structure of:

- Introduction with thesis and paper overview

- Literature review that covers what has been covered in the discipline and what is still missing.

- Method/archive

- Data (if your area uses a discrete section)

- Analysis (in my own writing this will often be the only section with subsections)

- Discussion/implications

- Conclusion

- References, notes, appendices, and figures. See the journal’s guidelines for specifics on formatting citations, figures, and appendices.

- The essay will more or less follow the structure of:

Any Taylor & Francis journal has a downloadable template for essays that makes formatting much easier. Other publishers and/or journals will provide a style guide in the author instructions section of their webpage and perhaps a template (it varies).

Style guidelines matter. My one (true) desk rejection for an article was for “not following the style guidelines” per the editor.

You will need to format two versions of the essay. One with the title page and all the information about you as the author(s). Authors will also have to produce a full version of the essay (with the title page and identifying information) and an anonymous version for peer reviewers. Taylor & Francis has a helpful guide on ensuring a submission file is anonymous.

Peer Review 101

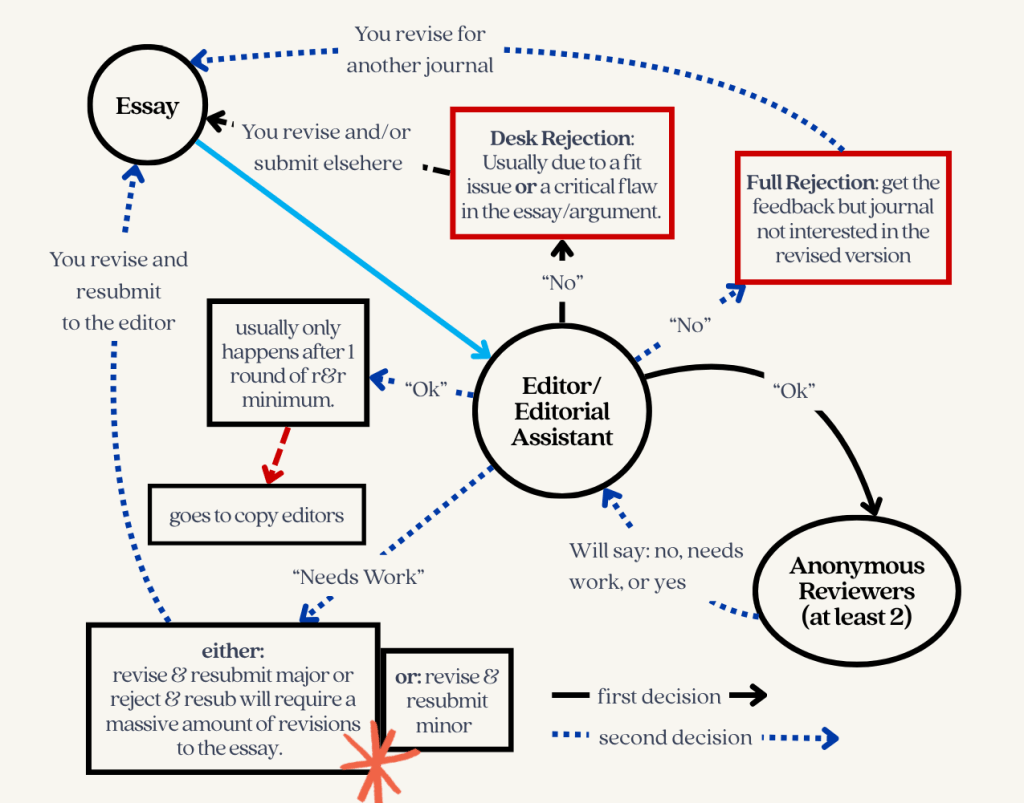

The diagram shows the general flow of a submission through peer review. (More detailed version here.) Typically, an article will go through at least two rounds of peer review.

- First decision: editorial staff decides whether the submission is 1) ready for review and 2) a fit for the journal’s readership. A no at this stage is called a “desk rejection.” Often, they are more about a fit for the journal rather than the quality of the essay.

- Anonymous review: if passed by the editorial staff, the anonymous version of the essay will go out to at least two peers in the field. They will have at least six weeks to do the review, but it rarely moves that quickly. Once the reviews come back, the editor synthesizes them for a decision.

- Please don’t call reviews “blind.”

- Review Decision: can be a rejection, a reject & resubmit, a revise & resubmit major, a revise & resubmit minor, or accept with minor edits. Revise & resubmit is the goal. (Hence the red asterisk in the image). Nothing is ever accepted on first pass, and nothing is ever accepted without at least minor edits.

- Revise & resubmit: revise the essay as you see fit. Include a resubmission letter that explains the edits made.

- Copy-editing & Page proofs: minor changes that ready the essay for press.

There’s a more in-depth post on peer review here.

Articles don’t happen overnight

Perhaps the “shortest” journey of any full-length article is the one currently under a second round of review, which is already closing in on 1.5-2 years.

In post-grad, it can feel frustrating how “long” something is taking to shape up or get to submission/publishable quality—or to get through review. That’s fine; it’s normal. Grads have been conditioned to produce multiple pieces of new work every ~4 months. Scholarship production cannot sustain that output without sacrificing the scholar.

You don’t need to publish “every year” once your first article goes out. You don’t need to only land in flagship or top association journals. Your arguments aren’t going to become passé if you take your time on the essay—people still write about long-dead presidents, for crying out loud. You don’t need to publish four articles in your first three years post-grad. Unless you literally have a tenure clock hanging over you that requires x number of things to make tenure in x number of years, you are not in a race.

Give yourself more modest goals.

- “I will complete one manuscript this calendar year.”

- “I will spend one semester reading/revising the manuscript.”

- “I will submit one article to a journal every two years.”

All of those would give you an excellent start to building a track record. Further, the more practice you have at inventing, drafting, submitting, etc., the more momentum you will gain.

Scholars who don’t perform “traditional studies” (e.g., observations, surveys, experiments) have a slight speed advantage in that data is not time-restrictive or -intensive. For example, my BBQ Becky article could have happened at any point after April 2018 when it was first uploaded. However, if I wanted to do an ethnography of the BBQing While Black events that happened in response, I would have needed to be *at* the event as it happened. But that still does not speed along the peer review and revision process that all articles go through.

It’s going to take time, and that is okay.

The next post will diverge slightly by jumping into how I begin research projects and work them toward an essay. A quick check-in: How are folks finding the series? What questions have arisen so far? Feel free to ask them below.

Leave a comment